Architectural Visual Analysis

Posted on: June 15, 2021

Written by Michael C. Abrams, Clinical Associate Professor at the University of Maryland-College Park and author of The Art of City Sketching: A Field Manual now in its second edition.

Architects study a site or a building through observation, reflection, and creative thinking. When we visit a site, we do quick sketches and diagrams to jot down our initial impressions and analyses. We use diagrams to isolate specific physical attributes and dissect a site. We also use sketches to express our feelings and represent our perceptions in a more intuitive way. This blog entry explores how to shift between the analytical and perceptual dimensions, which allow us to combine our sensory experiences with our rational thoughts.

“I have a real purpose in making each drawing, either to remember something or to study something. Each one is part of a process and not an end in itself” (Michael Graves, architect).

The Analytical Approach

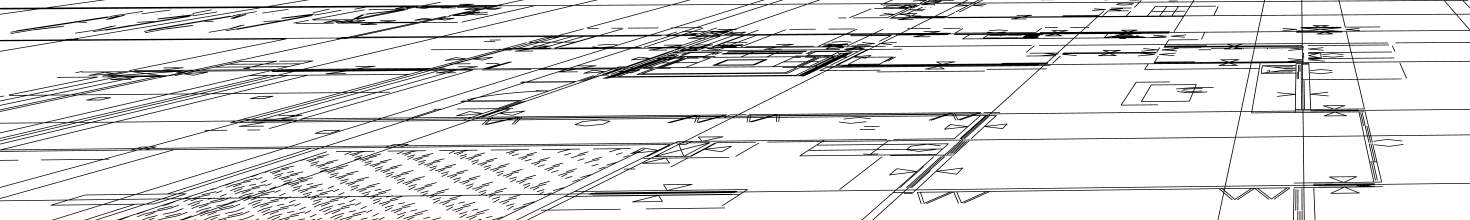

First, let’s consider the analytical approach to visual analyses. Start by observing, for example, the façade of a building. Through a diagram, architects investigate the height and width of the façade, as well as its proportions, geometry, architectural features, and number of openings (Figure 1). If we take a few steps back and observe the building, we will notice that it sits within a context that needs to be investigated and understood through site diagrams.

Site analysis calls for a more in-depth examination, including the site dimensions, the relationship of the buildings to the site and vice-versa, the traffic flow, and a variety of environmental considerations (e.g., sun and wind paths, flooding); see figure 2. Typically, these diagrams follow architectural conventions—they are represented in two-dimensions (e.g., plan, elevation, section) and/or three-dimensions (e.g., axons, perspectives).

The Perceptual Approach

Architects may also explore their subjectivity with a perceptual approach by using perspectives to document their personal reflections, as well as additional features of a site or a building. The Subjective Map and Chiaroscuro are useful perceptual drawing techniques to achieve this goal.

First, the Subjective Map method was created by Italian Architect, Andrea Ponsi to log and show a voyage of discovery through a city or a site (Figure 3). The map identifies spaces and objects encountered throughout a journey by shifting viewpoints and curvilinear perspectives, and also by showing spontaneous decisions on paper. The images on a Subjective Map fluctuate between the natural and the artificial, and from the practical to the abstract. It may include a bird’s eye view of a place, so it feels as you are flying over streets and buildings, or a worm’s eye vignette as you are looking up to the sky.

Second, Chiaroscuro—an Italian word for light and shadow—illustrates the character and atmosphere of a place at night (Figure 4). This classic technique, which was used by da Vinci, Rembrandt, and Caravaggio, offers a creative outlet to convey the effect of moonlight, candlelight, or artificial light on the built environment. Typically, dark background and white colored pencils are typically used to highlight surfaces and create dramatic effects. Through this drawing technique we can project a beautiful and yet haunting image, similar to the negative of a photograph. All in all, perceptual drawings—including the techniques discussed above—offer great flexibility in subject matter, in viewpoints, and effects. They can be precise or sketchy, and architects can experiment with different media such as pencils, markers, pens, and charcoal.

Conclusion

When combining analytical and perceptual dimensions on a visual study, we are able to explore the intricate relationship between the human eye, hand, and mind. Analytical diagrams not only help us analyze the built environment and understand how buildings engage with the site, but they also allow us to solve programmatic and environmental issues. By contrast, perceptual sketches capture the experience, views, and character of a place. Therefore, combining these two dimensions provide useful information for precedent analysis and the design process. These techniques are not only useful to architects, but designer, artists, and archeologists for instance could use them to combine the analytical and perceptual dimensions of their discoveries.

These two methods and many more are explored in greater detail in my book The Art of City Sketching: A Field Manual (2nd edition) by Michael C. Abrams. The Art of City Sketching: A Field Manual guides the reader through the process of free-hand architectural sketching and explains orthographic, diagrammatic, three-dimensional, and perceptual-type drawings.